History of the Alcazaba

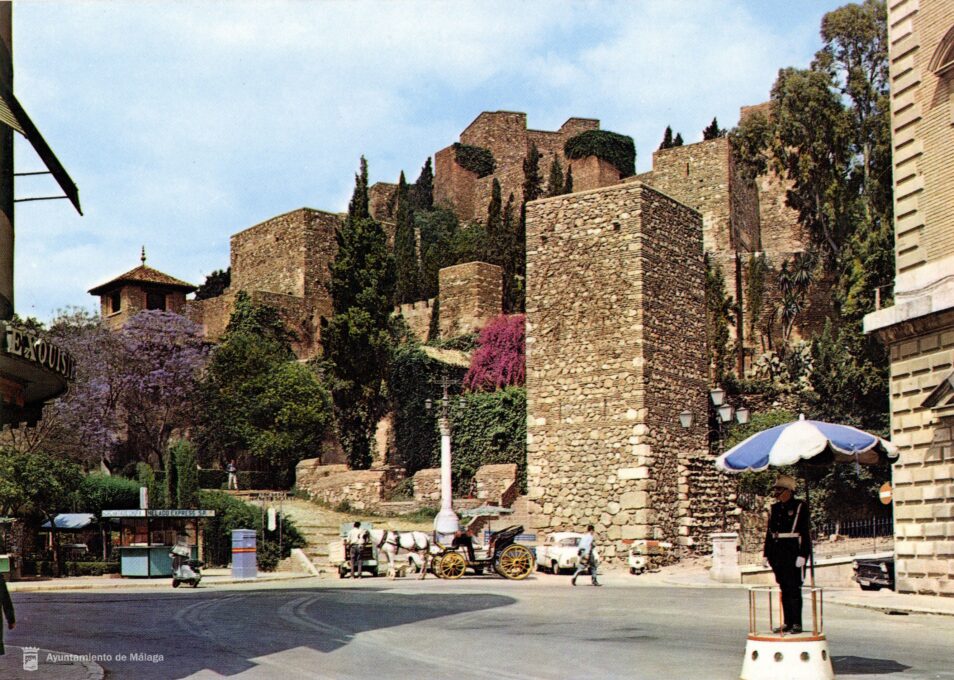

The Alcazaba, whose name al-qasba means “citadel” or “urban fortress,” was built by the Arab people for administrative, residential and defensive functions. It covers an area of 14,200 m², of which 7,000 m² are buildings, divided into 3,478 m² for the civilian area and 3,516 m² for the military zone. Located on the hill that rises towards Gibralfaro, its plan is completely irregular, adapting to the topography of the mountain in contrast to Christian castles, which tend to have a more symmetrical design.

Emirate period

In the year 755 Abd-al-Rahman I arrived in the peninsula and the Umayyad emirate began, Malaqa was part of it and it was at this stage that the Alcazaba was first mentioned as a fortress, as a source mentions that in the 8th century the construction of an aljama mosque was ordered inside it. This mosque is thought to have occupied the floor that today is known as the Plaza de Armas.

Caliphate period

The Caliphate of Córdoba began in 929 with Abd-al-Rahman III. Malaqa remained loyal to the Caliph and during the 100 years of the Caliphate the city experienced a prosperous period, but from this period the Alcazaba had only a few areas left with ashlar masonry work that were covered by the works of the Taifa period and later the Nazari period.

Taifa Period

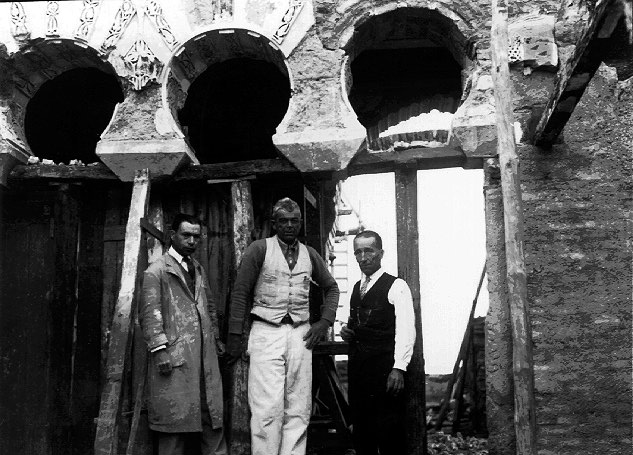

In 1014 the local rulers became independent from the central power and the different Taifa kingdoms began to form. In Malaga, the Taifa period began in 1016 when Ibn Hammud disembarked in the city on his way to Cordoba, executed the caliph and appointed himself caliph. In 1023 the third caliph of this new dynasty called Hammudi, Yahya, installed himself in Malaqa and the Umayyads recovered Cordoba. As we can understand, this was a very unstable period, where betrayal and assassination was the usual method of seizing power, and if we add to this the Christian advance, we can understand the rapid division of the territory. The fact that the Caliph Hammudí settled in Malaqa meant that the Alcazaba began to be built as the seat of power and became the palace residence of the city’s rulers. The triple arcade with alfiz and the first keep have survived from this Hammudid period.

In 1056 King Badis, king of the Zirid taifa of Granada, took Malaqa and expelled the Hammudids, annexing it to his taifa. A great deal of information about this period is available thanks to Abd-Allah, Badis’ grandson, who wrote his memoirs. In them he tells how the conquest of the city by his grandfather was not difficult, but neither was it very stable, as the population of Malaga revolted wanting to be part of the taifa of Seville and the resistance in the Alcazaba was the key to the city not changing hands.Badis reinforced the Alcazaba with a double wall and provided it with all the technical and military advances of the time, with a direct escape route to the port in case of emergency. He built a large part of the Fortifications of Entrance, the lower part of the fortress of the Alcazaba, among the most notable elements are the Puerta de la Bóveda and the Puerta del Cristo, both of which are bends, which increased the defence of the fortress. Badis also renovated the old Hammudid palace, building the pavilion of lobed arches. The keep was also strengthened and a gateway was built through it to the palace area, a different access from the main gateway and away from the city in order to be able to escape. This gate was sealed and walled with rammed earth in the Nasrid period. From this period also survives the residential quarter, equipped with a bathroom and a cistern, which was used to house some fifty high-ranking courtiers.

In 1056 King Badis, king of the Zirid taifa of Granada, took Malaqa and expelled the Hammudids, annexing it to his taifa. A great deal of information about this period is available thanks to Abd-Allah, Badis’ grandson, who wrote his memoirs. In them he tells how the conquest of the city by his grandfather was not difficult, but neither was it very stable, as the population of Malaga revolted wanting to be part of the taifa of Seville and the resistance in the Alcazaba was the key to the city not changing hands.Badis reinforced the Alcazaba with a double wall and provided it with all the technical and military advances of the time, with a direct escape route to the port in case of emergency. He built a large part of the Fortifications of Entrance, the lower part of the fortress of the Alcazaba, among the most notable elements are the Puerta de la Bóveda and the Puerta del Cristo, both of which are bends, which increased the defence of the fortress. Badis also renovated the old Hammudid palace, building the pavilion of lobed arches. The keep was also strengthened and a gateway was built through it to the palace area, a different access from the main gateway and away from the city in order to be able to escape. This gate was sealed and walled with rammed earth in the Nasrid period. From this period also survives the residential quarter, equipped with a bathroom and a cistern, which was used to house some fifty high-ranking courtiers.

Nasrid Period

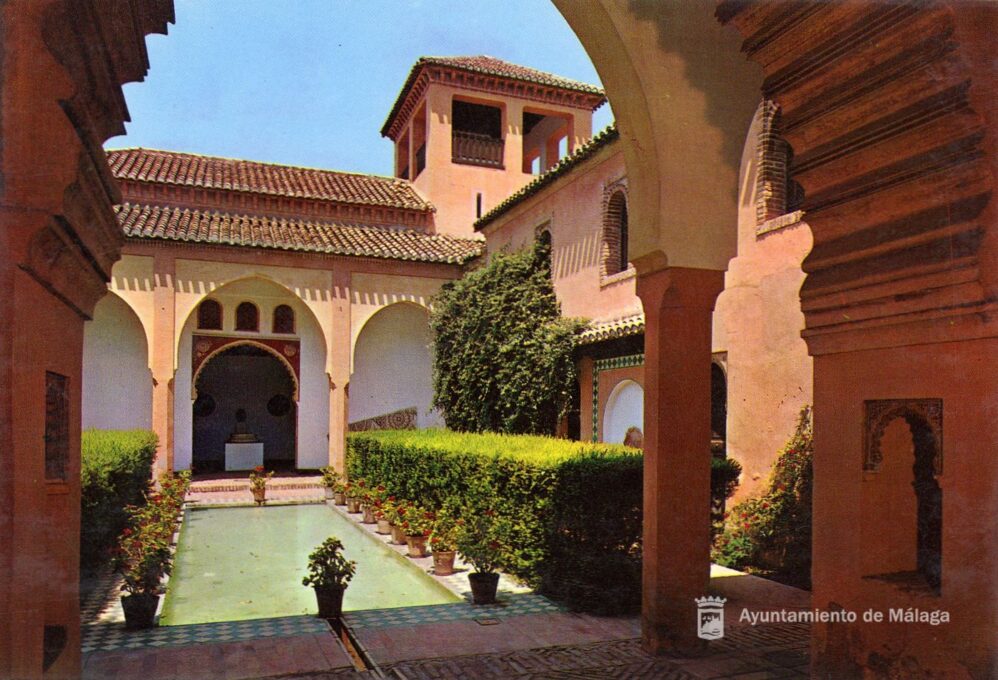

In 1237, Al-Ahmar entered Granada, marking the beginning of the Nasrid kingdom, which lasted until 1492 with the fall of the last king, Boabdil. During this period, the Alcazaba was significantly reinforced. The keep was enlarged and remodelled, and the new Nasrid palaces were built on top of the old palaces from the Taifa period. The most important change in fortification occurred during the reign of Yusuf I, who, aware of the advances in artillery, saw the need to protect the highest point of the mountain and built the Castle of Gibralfaro. To ensure safe passage between the two buildings, he connected the Alcazaba and the castle by means of a fortified corridor, known as La Coracha, allowing the Moorish people to move between them without external exposure. This work established the most impregnable fortification of its time, as confirmed by numerous written sources of the time that describe it precisely with this term.

Conquest of Malaga

On 5 May 1487, a contingent of 12,000 horsemen and 50,000 Christian infantrymen arrived in Malaga to conquer it. Ferdinand the Catholic was confident that the city would surrender quickly, due to several strategic factors. First, the shock of seeing such a vast army surrounding Malaga, coupled with the news that other nearby cities had already fallen or surrendered. In addition, the king employed a key tactic: allowing the population of the conquered cities to take refuge in Malaga, with the intention that the city would become overcrowded and it would be unsustainable to supply such a large population. However, he did not count on the fact that a large contingent of Gomeres soldiers, led by Hamet el Zegrí, was stationed in the castle of Gibralfaro.

These soldiers, aware that they could hold out inside the fortress, held out hope of receiving reinforcements from North Africa, as Malaqa was the main point of contact with North Africa. For three months, the defenders managed to hold out inside the fortress but, in the absence of reinforcements and the progressive depletion of supplies, a group of merchants from the city began to gain support for the surrender of Malaga, acting behind the back of Hamet el-Zegrí and his men. The surrender finally took place on 18 August 1487. The population asked to retain their status as Mudejars, but the Catholic Monarchs, exhausted by the long resistance, affected by the attack on their camp, and wishing to set an example to the next cities to be conquered, rejected the request.

After the conquest, the fortress was left in good condition, which allowed the Catholic Monarchs to establish it as a base for the last campaigns against the Kingdom of Granada. Subsequently, the complex served as a strategic supply point for the wars in North Africa and as an important coastal defence against attacks by Barbary pirates.

15th century

During the 15th century, the Alcazaba became the residence of the new governor, conserving its defensive character and its function as the seat of the city’s government. On 30 August 1494, the Catholic Monarchs granted Malaga its coat of arms, in which the monumental complex was included as a prominent symbol. Such was the importance of this fortification for the Crown that, in 1496, part of the tithe on lime, tiles and bricks was earmarked for its upkeep. Among the initial alterations, the main entrance was made easier, which is why the entrance lost its original curved structure.

17th century

In the 17th century, due to the weakening of the Spanish empire, Malaga became a strategic military frontier against Turkish and French attacks. In 1618, a report by the warden, and in 1622 another by Martín de la Roa, confirmed the good state of the Alcazaba, which meant that in 1625 this fortification was used as a royal lodging for King Philip IV during his visit to the city.

18th century

Around 1700, the governor’s dwelling was moved to the lower part of the Alcazaba, where vaults were built to support several floors for military administration, and the governor’s residence was established above the Gate of Columns. This change in layout marked the beginning of the abandonment and subsequent deterioration of the upper part of the fortress.

In the 18th century, with the advances in military techniques, Charles III declared the Alcazaba useless and ordered its demilitarisation. From then on, resources were allocated exclusively to Gibralfaro Castle, which continued to serve as a barracks. In 1749, the Alcazaba was transformed into a prison for gypsy women and their children, housing up to 1,200 people, although only for two years. In 1786, the Alcazaba was transferred to Malaga City Council.

19th century

During the 19th century, the structure of the Alcazaba began to be occupied by the civilian population. In 1820, 113 dwellings and 431 residents were documented inside. Some of these buildings were built under licence, although most of them were self-built using materials from the fortress itself. Between 1874 and the beginning of the 20th century, the authorities showed a continued interest in demolishing the Alcazaba in order to level the hill and open up direct access between the port and the city.

20th century

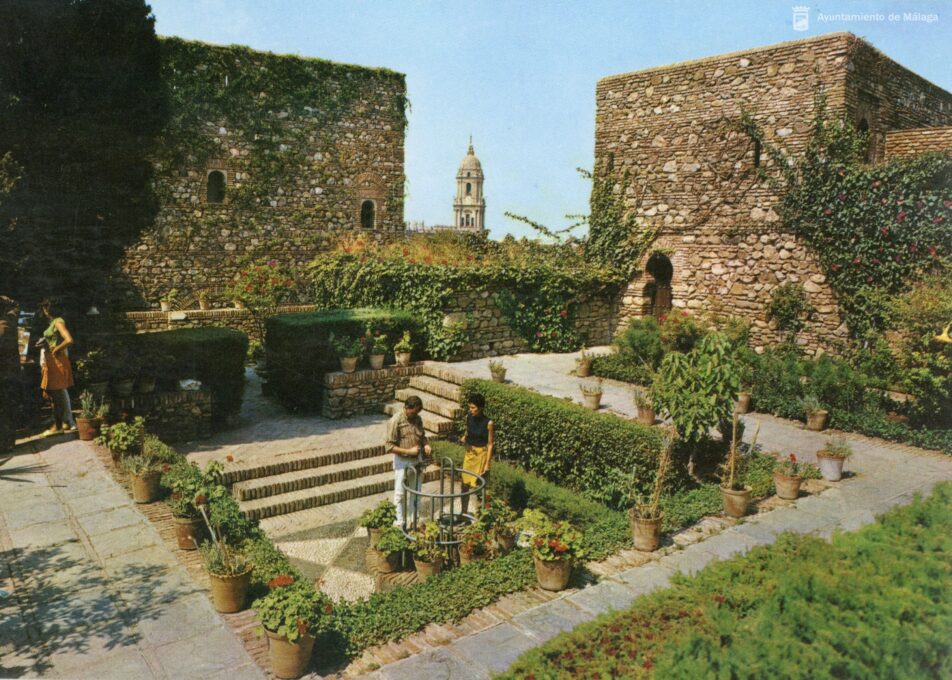

By the early 20th century, the Alcazaba had become a slum, inhabited by poor families with no access to electricity, running water or sewage. The demolition project was gaining more and more support, but in 1931, the Alcazaba was declared a Historic-Artistic Monument and became part of the National Treasury, which guaranteed its protection. This prompted the historian Juan Temboury Álvarez to take an interest in the monument. In 1934 he managed to get the first restoration work started. Restoration began in the parade ground, and the team soon discovered the magnitude and historical value of the monument, which allowed the restoration permits to be extended. In 1937 work was carried out on the palace’s living quarters for study and preservation, as it is perhaps the most important archaeological part of the palace. This housing area is not currently open to the public, but special mention should be made of it in the following link to the housing area. The restoration work lasted until 1968, when it was finally completed. In 1946, a request was made to the State to create an archaeological museum in Malaga, and the Town Hall proposed that it should be located in the restored areas of the Alcazaba. Thus, visitors could enjoy both the monument and an archaeological collection from the province, including ceramics and materials found in the fortress itself. The proposal was approved in 1947, and the Alcazaba became an archaeological museum for almost 50 years, until the collection was transferred to the current Malaga Museum in the old Palacio de la Aduana.

Since then, the Alcazaba has undergone a continuous process of conservation and restoration, which allows us to visit it as we do today.